(This blog is a draft version of an essay soon to be posted on Esri Storymap under the name of “Monster Hunt: Spatial Representation of Gendered Monsters.”)

In our deepest nightmares, monsters haunt us. Monsters terrify us with their grotesque bodies, supernatural ability overpowering human strength and paranormal movements. Their existence as well as their heinous actions mock human attempt to understand, grasp, and pin down what they are. So, humanity’s hunt for monsters begin.

When just about to catch them… they escape!

They escape humans not only intellectually but also spatially. One cannot catch a monster easily. It gets away just when one is about to seize it and turns into a smoke or appears to have traveled thousands of miles a way in a second. Typical monsters that easily come to mind such as Count Dracula or the Creature from Frankenstein are particularly threatening because they move about the globe so effortlessly. They dart in and out of European countries let alone the “mysterious” East and Africa.

They are everywhere: globally roving about but also at home.

However, there are other monsters who stay local and threaten relatively small number of people. Female vampires who do not leave the castle, witches who demonize neighbors, ghosts bounded to houses, a creepy man-killing cat rambling around a deserted fortress, etc. The fear that we have for this type of monsters are quite different from wide-roving creatures. Interestingly enough, it seems these local monsters are usually female: “Cats,” “weird sisters” of Stoker’s Dracula who can’t hunt for themselves since they are imprisoned to the castle, a victimized female ghosts seeking revenge. This project starts from a question whether gender plays a role in special representation of a monster and looks to find a connection between spatial patterns of a monster and the specific type of monstrosity monsters embody.

Monsters and sympathy

Investigating monster literature is an extra-ordinary job. We don’t just get “scary” tales in literature; we get a glimpse of what it is to be a monster. Take Frankenstein for instance. Unlike popular adaptations that prioritize the horrific appearance of animated corpse of the Creature, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a text of interplay between various perspectives. Not only do we get Dr. Frankenstein’s narrative creating, escaping, tracking the Creature’s horrific murders, but significant chunk of the narrative devoted to the Creature and his side of the story. Being born (in most shocking way possible–electronic jolts!), abandoned immediately in cold and dirt, lost in the world (literally), seeking love and connection, brutally ostracized, feeling nothing but rage to revenge on his creator. As many critics have noticed, the eloquence of the Creature gives his narrative the level of sympathy that deserves questions regarding the intention of the author. And as many great literature does, it asks questions about the meaning of monsters and monstrosity. The narrative is set in a way that the readers can sympathize, or at least understand the reasons for his monstrous actions (murdering of a little kid, wife and best friend of his creator). Is he a monster if the society made him the monster?

Pertaining to this project, the travel the Creature initiates is actually driven by the society. He is banished from one home to another only to be kicked out of to another place. He cannot stay in one place because he cannot be a member of any society. Though he is made of human, made by human, speaks human language, he is an eternal exile bound to be around the world. Even his later journey is caused by the “war” between him and Dr. Frankenstein–a war between the creator and the creature–one the Creature would want to avoid but has to face now. Two characters chase each other all over Europe and even to the North Pole.

As seen in this case, the monstrosity of a monster is intricately tied to the location and the journey. The creature becomes (aware of the fact that he is) a monster as he changes location and commits sins. Within a Gothic castle of Frankenstein, he is a gothic monster of action who is hidden, appears, and kills. At the warm cottage environment of De Lacey family, his monstrosity pertains to the surprises the family members feel looking at his body. Even though he is a same “monster,” the type of monstrosity perceived by the characters is geo-spatially distinctive.

And as interestingly, this has a fascinating relation to the level of sympathy. For Count Dracula, it might be argued that the level of sympathy characters (or even readers) feel is lower because he comes from a far away land. He wears strange garments, speaks with an accent, and emanates weird energy. It is his foreignness that distracts the sympathy from others. Is the Creature more sympathetic character because he is “one” of “us?”

So here are the questions this monster map explore:

- Central Question: Does gender of the monster affect the distance traveled? How is the distance related to a level of monstrosity and level of sympathy?

Do female monsters show smaller trajectory and consequently lower level of monstrosity than male monsters? Do they have different habitation patterns than male monsters? How does spatial representation affect level of sympathy? Will the gender of the author complicate any pattern?

Will we find any unexpected patterns of monsters with this visualization? Let’s hunt some monsters then. But first… who are on the menu?

Monster Corpus

Now here’s a table of my monsters. Unsurprisingly, these are monsters in fiction. Yes, we do have monsters (supposedly) in real life. But here I use literary figures to explore how these literary representations because the purpose of this project is not really hunting monsters but to capture the essence of a specific culture and to enable a cultural analysis. How did people imagine a monsters to be like? Did they come from far away land or did they stem in our own soil? Did they move like the wind and disappear like the air or are they just stuck to one location? For future studies, analyzing oral histories would be interesting. But for now, I’m sticking to literature–the land of imagination filled with juicy layers of cultural perspective.

Included in the database are eighteen texts with thirty characters in total, fairly balanced between gender of the monster and author’s sex. We have seven male monsters by male authors, nine female monsters by male author, six male monsters by female author, and finally seven female monsters by female author. In addition to the gender of the monster axis, I added author’s sex mainly to test whether there’s any interesting pattern that comes out of it. Texts include Gothic literature, Ghost literature, and other horror literature that features in-between humans, animals, witches, etc. mostly from nineteenth-century literature.

Now, before we start hunting down these monsters, let’s first map out where they appear.

Now, before we start hunting down these monsters, let’s first map out where they appear.

The actual monster map (dozens of them compiled for the convenience of our hunt)

As the esri Storymap is in-progress, I embed a video clip that walks through an ArcGIS map (desktop version). Start at 00:45.

** As of September 1, 2021, the video is NOT working for the purpose of converting data into Esri Storymap. You can still watch it, but there’s no sound.

Male monsters vs Female monsters

- Features: Points are marked when a character is mentioned/indicated to be at such location, and lines demonstrate their travel trajectory. This line also allows the measurement of distance traveled. As will be shown later in the video, the krigging effect shows the level of monstrosity in a visualized manner. Simply, the redder the place is, the more monstrous a monster is.

First, we have a map that visualizes sightings and movements of male monsters by male authors. As you can see, they move globally and travel relatively large amount of distance. Part of the reason for the anxieties characters within these texts (and of course, for readers) is that they can never understand how monsters move so much distance at once. Combined with xenophobic fears in those eras, that they move about the world so effortlessly doubled their monstrosity.

The visualization is strikingly different for female monsters created by male authors. If male monsters by male authors showed large bounding of movements, female monsters by male authors show lesser degree of movement. The one long line that stands out here–which shows a movement from Paris to Damascus, Syria to Mauritas in Mauritania–is from Succubus. If we take this out as an outlier, the general pattern here is that female monsters almost never travel outside of her country. Their movement is well hidden from a large map and is almost invisible from this view (01:25). But if we zoom into the layer, we can see that female monsters actually move about but only to such a small degree that it’s not recognizable at the level of world-view map.

The problems of scale and what’s up with “measuring” monstrosity and sympathy?

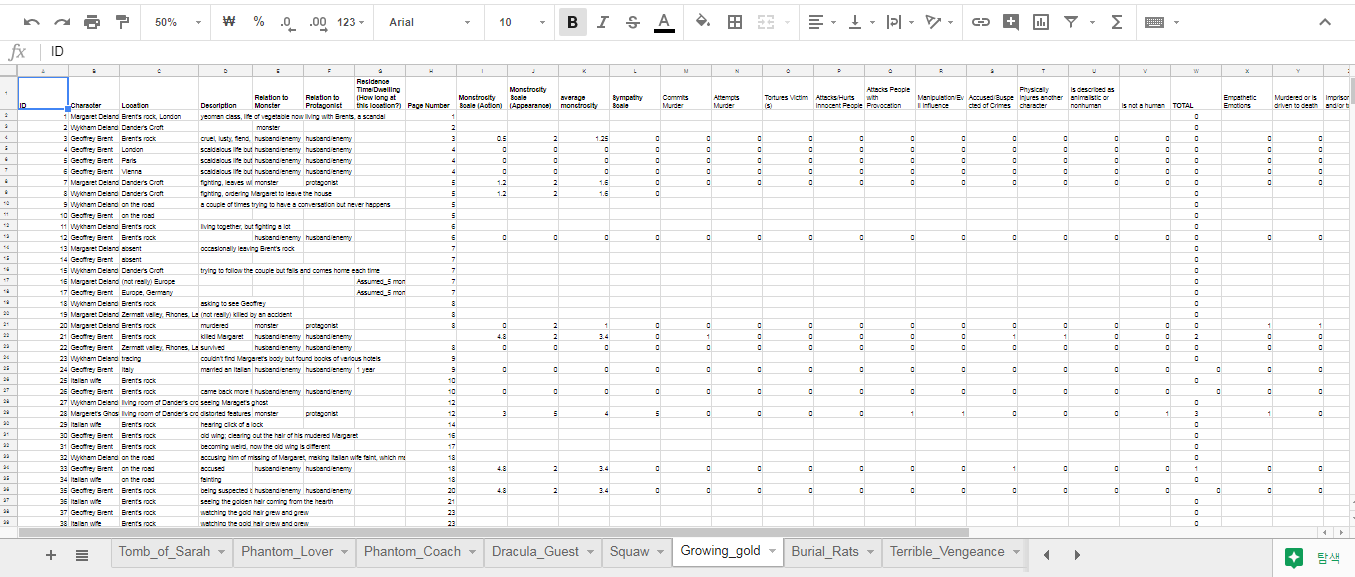

As can be seen later in the video (03:00), the krigging effect shows the level of monstrosity. Like the travel journey of female monsters that couldn’t be shown in a large scale map, monstrosity of female monsters has to be zoomed up close to be seen. Because this map does not show the sequence of narrative it is not easy to see just by looking at the map what exactly happened or what made the monsters “red.” In the actual ArcGIS map, the users can click around each point to see the details of such information. The text title, gender of the monster and author, name of the character, the monster’s relation to protagonist, what happened at that location, etc. But even with this information, how did I measure monstrosity or sympathy? Isn’t that subjective response each reader has? How can you numerically tell the level of monstrosity? Is there a scale or a level for such thing?

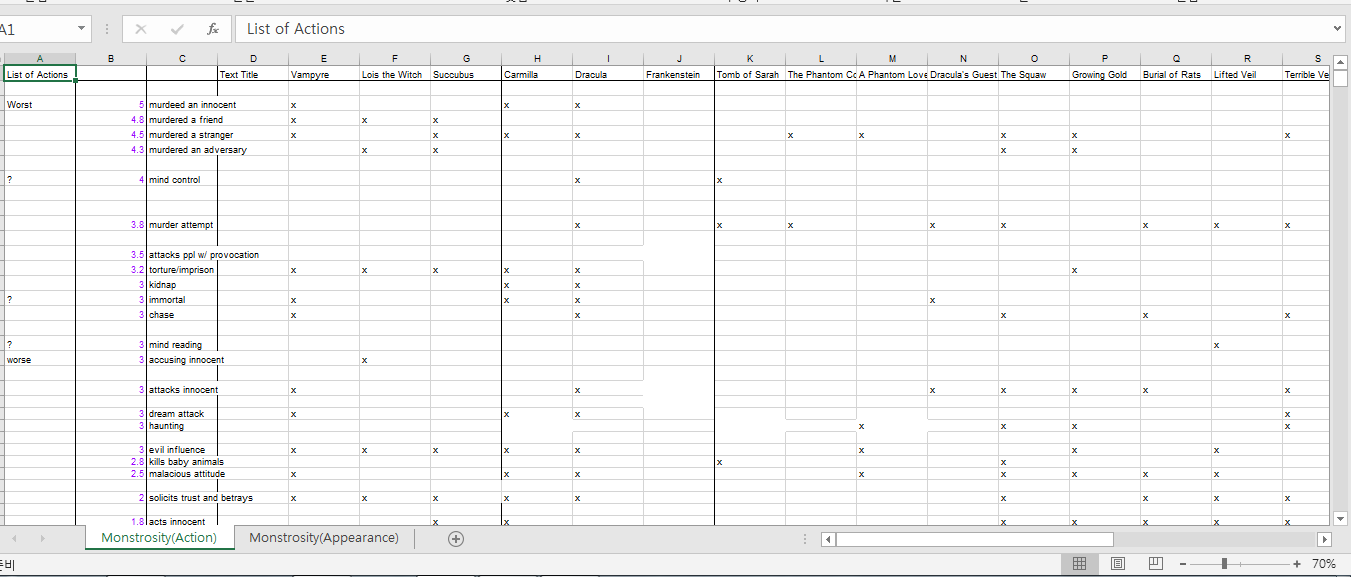

Yes and No. To talk about the rubric, I first have to talk about how this project started in the first place. This monster map developed out of a group project that began back in 2016 lead by Dr. Ellen McCallum and Ed Schools. I had three undergraduate teammates under the name of “monster team.” Because we could not find a “canonical” monster level, we decided to come up with one for our map and made up a totally arbitrary one. Ex. If a monster murders an innocent, 5.0 on the monster level which is the highest. If a monster just stalks a character, 3.5 on the scale. Metamorphosis? maybe a 3.0. As we made up this rubric, we realized that we should have two categories at least. One for action and one for appearances, and we averaged the two to get a final monstrosity level (Again, questions arise: why 5:5 for action and appearance? Isn’t action more meaningful? Isn’t appearance what’s more significant in terms of defining a monster? Well… these are the questions we had to let go). Some of the description was hazy and we had to decide if “metamorphosis” is a monstrous action or appearance. But without a few exceptions like this, it was a quite clear categorization. Below is a screenshot of my monster rubric. On the left we have a scale from 0 to 5 each action or appearances attached to numerical number. Total 27 actions for monstrous action category from being just “creepy” to murders. Other actions include “dream attack 3.0,” “evil influence 3.0,” “intimidation 1.2,” “mind reading 3.0,” etc. Surprisingly, there aren’t whole lot of things a monster can do. Only about 27 types of actions. (Does this suggest Gothic/horror genre texts even in 18th and 19th century became formulaic?)

Of course, doubts arise. How would you assign “intimidation” (1.2) as something less monstrous that “dream attack” (3.0)? Sometimes, “torture/imprison” (3.2) is worse than “mind control” (4.0). And this is where we step away from distance reading go into close reading, or at least, reading. What I decided I’d do is to read all of the text and check and adjusted the scale in order to make it more “universal” to all the text I had. I had to make some compromises to incorporate different levels of monstrosity. Sometimes, the description or the attitude of the narrator toward a monster who only “chases” (3.0) a character is so hostile that it is scarier than a matter-of-fact “murder of a stranger” (4.5).

And as I had doubts that maybe making up a monstrosity rubric wasn’t a good way to “distance read,” I came across a surprising phenomena. As a group, we all had similar scale set up. Every one of group member was working on different texts and thus, supposedly different rubrics. But when I went into read their text to change whatever was necessary on the rubric, I found that I had very little to challenge. Maybe the texts we chose were ones that leads to more general response. Maybe I was already prejudiced? I even developed my own rubric and compared the differences of the overall averages of monstrosity level but the differences were ignoble. Surprisingly so. Maybe we have this fantasy that each individual’s reading experience is so unique and subjective that we can’t come up with a universal response. Are we ignoring the fact that writers (sometimes…or usually?) intend to create a general response? Well, at the very least, a horror genre writer wouldn’t want the reader to find the text funny. A murder is supposed to be more dangerous and horrific than just killing a baby animal. How else do we have legal penalty system? But again, it is literature not laws. It could be argued that Mary Shelley has the Creature and Dr. Frankenstein chase each other for what seem like ages than just murdering confrontation because it would be more “monstrous” to have this constant influence over one another’s life. Some big theoretical questions remain in making the rubric…

Results: the gendered of monsters!

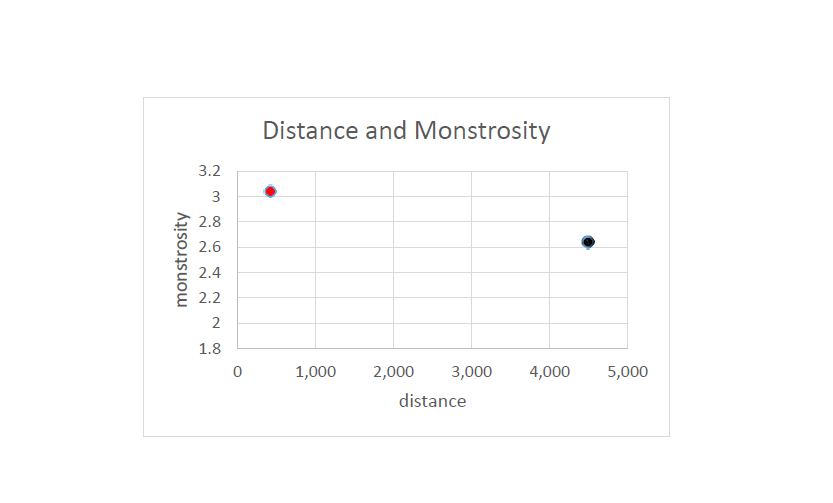

Based on the distance analysis, the average distance of monsters have start difference according to gender. Female monsters traveled on average 423 km whereas male monsters traveled 4495 km. As expected from the visualization on the map, male monsters travel about ten times more than female monsters. On the other hand shows that female monsters show a slightly higher level of monstrosity. Considering that appearance and action assigned to 2.5 and 3.0 monstrosity have significant difference, this could be seen as a rather meaningful difference. On monstrosity-action scale, malicious attitude is counted as a 2.5 while 3.0 includes kidnapping, chasing, mind reading, accusing innocents, attacking innocents, dream attack, haunting, and imposing evil influence. For monstrosity-action scale, 3.0 monstrosity is described as one that’s not human but perceived as or disguised as human whereas one that’s human but little different or ugly is a 2.0 monster.

It then seems then female monsters travel less but show higher level of monstrosity when male monsters travel much further but is perceived as less monstrous. Below graphs shows distance measurement and monstrosity level of monsters categorized by the gender of the monster and author (ex. MM: Male monster by Male author).

What to make of these pattern?

One conclusion we can draw out of these result is that the types of horror male monsters and female monsters elicit are quite different. If male monsters threaten the globe infecting, killing, and haunting everyone, female monsters are local getting revenge to those around her.

One common feature of female monsters, which greatly heightens their level of monstrosity, is their sexuality. Although sexual aspect of male monsters such as vampires is seen as dangerous, this characteristic is not shared by many male monsters. For female monsters, they all emanate or evoke sexual energy and sometimes it is the only “evil” aspect of their monstrosity. Lois’ monstrosity mainly stems from the fact that she is beautiful and that she excites sexual desire in two religious men. And allegedly, the only wrong of succubus is her strangely excessive beauty that “shed[s] . . . joys around her” (312). Makala maintains that monsters–ghosts in particular–of nineteenth-century are an avenue for women writers to articulate their experience of ‘social terror’ against patriarchy (54). If eighteenth-century’s persecuted maidens traveled through labyrinths and dungeons of a debilitated castle and proved their physical strength and mental power (Moers 129), this heroinism is transferred into female monsters and ghosts. Strength and power of females that could not be expressed under normal circumstances of patriarchy was inherited by female monsters. Female writers place the placeless—monsters—sexual desire, frustration against patriarchy, injustices—in a much dramatic form of a “monster.” They do not have to travel much far to show their monstrosity. They stay within the bounds of the domestic house (or neighborhoods—extended “home”) brandishing their failure to be placed within existing society.

Spatial representation of monsters shows interesting differences between gender of the monster though it is complicated when the gender of the writer is included in the discussion. By taking a broader and higher perspective than the group mapping project, this project could discern meaningful patterns of monsters in terms of distance, locations, boundary of movements, and how these spatial elements are connected to characteristics of monstrosity and sympathy monsters demonstrate. The result of this project gives valuable support for humanistic approach of horror literatures validating the difference between gender of the monster and authors and their intention in creating such monsters.

Spatial analysis of this horror literature not only confirm traditional readings of texts but also brings insight to “outliers” that do not fit into the larger schema. Texts such as Frankenstein and Lifted Veil are interesting outliers of female works which have their monsters travel great distance with low-average monstrosity. Considering that Frankenstein is one of the most often referred text that brings controversy to the definition of “female gothic,” its unique spatial representation of the creature is another element that deserves further investigation.

We know their pattern… now what to do? How can I share it to the world?

Now that we’ve studied monster’s habitation pattern, it’ll be best if we can share this knowledge to the world. I’m developing a storymap on Esri website to publicize this map. As I used desktop version of ArcGIS, I first had to transfer my data to online ArcGIS account through which I can create layers of map that are translatable to storymap.

This turned out to be a difficult job. Since Online ArcGIS is like a free try-out version, it doesn’t support many of the complex analysis I had embedded in my map such as grouping layers ad krigging analysis. And because it doesn’t support grouping layers, I had to take individual feature in different export data. Say, I had “MM map” consisting of points, lines, krigging, minimal bounding of 8 different characters. It means I had 32 different features compiled in one map. In order to transfer that one map, I had to export each and every feature in different file so that online ArcGIS recognize that file. On top of that, because my meta data is so large (30 columns with more than 700 rows), online ArcGIS is keeps giving me bugs. As I mentioned before, my meta data includes text title, gender of the monster and author, name of the character, the monster’s relation to protagonist, what happened at that location, page number, duration, published date, any important things to note, etc. And when one hovers over or click each point, it should generate a information table that tells the audience what that point means. Without it, it’s just a point on a map. Unfortunately, Online ArcGIS is not allowing me to do that for some reason I still have to figure out.

Thus my failure. What is DH without years of failure, errors, and staring blankly at the dataset and coding logics! Besides, working with storymap was also fun. I put a lot of thought picking out style/format of my map and decided to pick one that is best to embed long essay with the map at the background. This style I chose also allows the audience to be interactive with the map zooming in and out to see where monsters are seen.

DH and Computational methods: it’s not the objective truth

Uncertainties, assumptions, compromises and continued challenges

- Uncertainties/Assumptions: With mentioned compromises above, almost in every text, there are pointed locations that are based on assumptions. Moreover, the range of accuracy vary from point to point. For example, in Lois the Witch, I used two historical maps of Salem to indicated sites of prison, execution place, courts, etc., but locations of character’s houses were selected randomly out of several points of residents. The difference of scale should be noticed since there are large differences in detailedness of geographic information. Whereas texts like The Succubus gives out even street names, The Vampyre or “Tomb of Sarah” sets its characters in large settings such as “Rome,” or “Greece.” Fictional spaces were also mapped within a larger context of the text. Even when ‘Dwoldling,’ a set place for “Phantom Coach” turned out to be fictional, it was mapped according to the information that it was 12 miles from ‘Wyke,’ a moorland far north of England. Besides, the distance traveled is mainly conjectured out of a straight line connected between each point of location.

I also had the conflict between my two selves–a humanities scholar who wants to challenge things and the author of this map who wants to visualize my map in the best way possible. I have my male monsters in green and black and female monsters in pink and red. I have to say I still doubt whether this was a smart choice. But I had to pick my battle. Since I am publishing this to a general public, I thought I’d use colors that best visualize the purpose of my map–compare and contrast between genders of monster.

Where to go now

I plan to publish this storymap online and polish it enough to enter it into storymap contest. I’ve looked through past year’s winner and looks like there’s no category for “fictional” maps. Usually it’s travel, history, migration, etc. with one honorary fictional map that a dad and 5 year-old girl made. I’ve also received feedback from my colleagues that many of them would like to use this as a pedagogical tool when they’re teaching. Not only for classes that read gothic novels but also for theory class as well. What does it mean that we don’t usually track down locations and look at maps when we read novel? Does it mean that readers are distanced from imagining those situations less realistically? Does that enhance a sense of horror? Or does it hinder it? This map doesn’t just “hunt” monsters. It’s a question mapped out: of genre, characterization, visualization, and above all, reading experience.

Special thanks to all the contributors and advisors who made this happen.

Thank you Monster group teammates, Dr. Ellen McCallum, and Ed Schools!